What is Collective Guilt? And is it rational?

One aim of my current research project is to understand the nature and value of collective guilt. This kind of guilt often gets talked about with respect to historical injustices. Germans, for instance, are often said to feel collective guilt for Nazism and its crimes, including The Holocaust. People from the United States of America sometimes report feeling collective guilt about the historical injustices their ancestors committed, such as the transatlantic slave trade. And British people sometimes report feeling collective guilt about British colonialism and imperialism and its many wrongs. There is then sometimes push back that such feelings are in some way inappropriate. No one alive committed those heinous acts after all! Or were they really just not as bad as they seemed? Or maybe it is just pointless or counterproductive to feel (or claim to feel) collective guilt. In this post, I want to look a bit more closely at the nature of collective guilt, pointing out how it may sometimes be rational to feel, its potential value, as well as its potential dangers.

The Nature of Guilt

In my first post, I outlined an account of guilt. In my view, guilt is not a moral emotion.

Guilt is still a response to a perceived failure of some kind, but it need not be a moral failure. For example, we might feel guilty because we perceive that we have failed a friend through failing to meet an unreasonable and unknown expectation of theirs. We’ve failed a friend by their standards, and sometimes knowing this is enough to make us feel guilty for something we’ve done or have failed to do.

Guilty feelings motivate us to act in particular way, but it need not motivate any obviously moral behaviour. While guilty feelings might motivate a morally adequate apology, they may also motivate a hollow apology (e.g., one that simply aims to get our friend to forgive us), or it may instead motivate us to be defensive and criticise our friend for making us feel guilty (e.g., because their expectation is both unreasonable and unknown to us, so they cannot justifiable hold us to it). I didn’t say this in the earlier post, but guilt may also motivate us to suppress our feelings — perhaps through alcohol or drugs, but even just through merely not attending to our guilty feelings and focusing on other things instead.

In summary, then, guilty feelings have the following three core features:

Appraisal: they involve an appraisal of an action as substandard in some way, whether from our own perspective, the perspective of another, or from an external perspective, such as the perspective of society or the perspective of morality.

Affect: they feel bad, and in particular about something we have done (or have failed to do). We may also feel small or worthless (feelings which may sometimes make us resent the person who makes us feel guilty).

Motivation: they motivate us to get rid of guilt, and so may lead to a morally adequate apology, a hollow apology, defensiveness, suppression, or even a combination of each.

What makes the difference between guilt that motivates a morally good course of action, such as offering a morally adequate apology, and guilt that motivates a morally bad course of action? In my view, the difference lies in how we attend to our guilty feelings. Sometimes we might get defensive because we do not take the grounds of our guilty feelings to be adequate. This might be justified in some cases, such as when a friend holds us to an unreasonable and unknown expectation. In other cases, we might attend to what causes our guilty feelings — such as our apparent failure, the (actual or imagined) negative judgement of a person (which may be ourselves or another), etc. — and try to rectify the failure and so try to change person’s judgement from a negative one to a positive one.

Unlike individual guilt, collective guilt isn’t about a person’s own actions. It is rather about an action of a collective that one is a member of. Before turning to collective guilt, we therefore have to know what makes something a collective action (is there even such a thing? you might wonder) and what makes someone a member of a collective.

Collective Action and Membership of Collectives

Actions are performed by agents. Agents are entities that perform actions. While both true, they don’t help to explain either concept in a way that gives us any useful information. Action is defined in terms of agency, and agency is defined in terms of actions. If you’re not sure about either, it’s hardly clearly by defining one in terms of another.

I won’t want to delve into such questions here, though, and will instead simply take for granted that there are actions — that is, events caused by agents in a distinctive kind of way. For example, the way we might raise our hand because we intend to do, as opposed to our hand being raised because a gust of wind moves in the air. The former is an action, but the later is not — it’s something that happens to us, and not something we do.

I will also take it for granted that there are agents — that is, entities that can act, (or, to put in a more linguistically laborious way, entities that can perform actions). Human persons are the most obvious kind of agents. We take it for granted that we can act — that is, that we can bring about things in the world in a different way than, say, the wind or an avalanche can. But can there be collective actions?

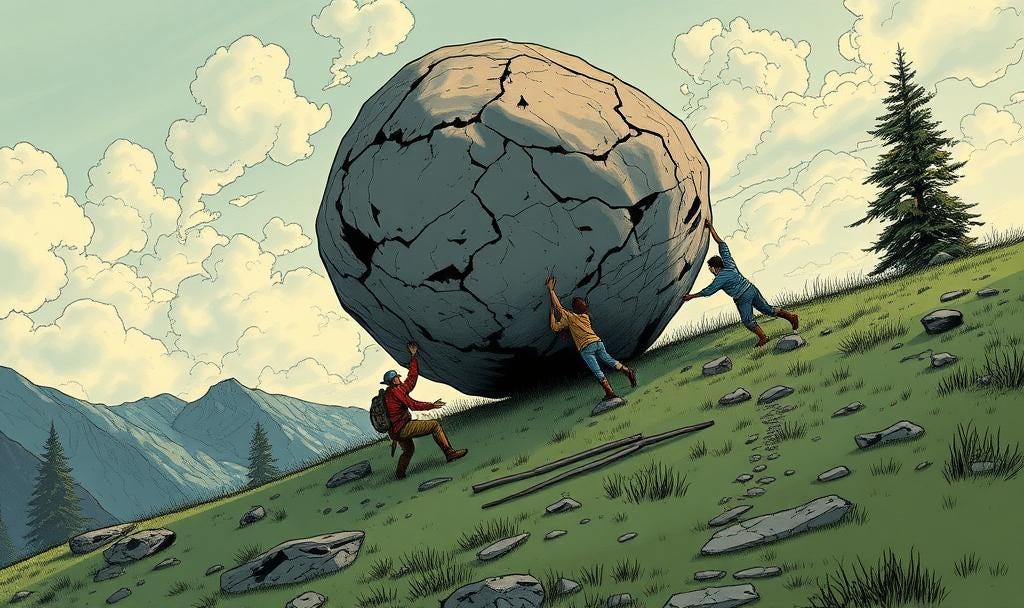

There are different ways of understanding collective actions. The first conception — call it The Contributory Conception — involves people working together to bring about some end. Members of the group are just those that work together to bring about that end. For instance, suppose five people work together to push a boulder down a hill. It might be that each individual person lacked the strength to move the boulder. But, working together, they can combine their strength to bring about a particular outcome: the rolling of the boulder down the hill. This outcome, on this understanding, is a collective action. It is an action brought about by a group of people, a collective. On this understanding, a person is a member of a collective through taking part in bringing about an event (such as the rolling of the boulder down the hill). On this view, the collective action is brought about by the joint or combined agency of each member of the collective. In the case above, members have both knowledge of what each member is doing, they each intend to bring about the same end, and are all explicitly working together.

We might also consider variants where people are contributing towards some end.

First, suppose five people know what each one is doing but are not explicitly working together to roll a boulder down a hill. We might suppose that each person is hoping to be the person who rolls the boulder and feels they are competing against, rather than working with, others to roll the boulder down the hill. Even so, they each might contribute towards the boulder rolling down the hill.

Second, suppose five people are each aiming to bring about some end, but do not know anyone else is also trying to do this. Five people might together push a very large boulder without knowing anyone else is trying to do so. They each want to roll it down the hill, but each person thinks that they did it alone. However, they really unknowingly worked with others to do this.

Third, suppose five people are contributing towards bringing about some end, do not know anyone is doing so, have no desire to work with anyone towards this end, and even do not want to bring about this end. We might suppose that five people are all leaning on a very large boulder and then manage to roll it down a hill. Even though they do not intend to roll it down the hill, each has still contributed towards bringing about that event.

The last variant is especially important in understanding how people can contribute to supporting cultures (or climates/atmospheres) that can help to bring about wrongful actions. For instance, people might unknowingly support a racist culture that contributes towards racists actions — perhaps merely through having racist attitudes. They might do so by, for example, not calling out other people’s racism, laughing awkwardly at other people’s racist jokes, and perhaps even by trying to call out racism and provoking a backlash that brings about more racism. We can all contribute to such cultures regardless of how we view such cultures and regardless of our aim to undermine such cultures. We can be members of even such a potentially disparate groups simply through even minor causal contributions to a wrongful action, whether it is a proximate causal contribution to an action or a more distant causal contribution (such as one that supports a culture that then contributes towards a later action being performed).

The second conception is The Agential Conception. On this conception, a group of people constitute an agent above and beyond their own joint or combined agency. There are (at least) two forms of this conception. The first captures collective actions that result from institutional contexts, whereas the second focuses on contexts without a formal decision-making process. (Arguably, though, both could be replaced by considering people’s causal contributions — but I won’t argue of this here.)

The first form holds that collective actions are brought about by collective agents. Such agents are made up of individual agents — that is, of people — but the agency of the collective is not reducible to the agency of its members. It could be, for instance, that more members disapprove of what the collective agent does, but the collective agent acts nevertheless. This model of collective action is particularly suited to understanding how some institutions, such as corporations or countries, can be thought to act. Such institutions have formal decision-making procedures and the actions of the collective result from these decision-making procedures. A corporation, for example, has a board and a management structure. These subgroups are responsible for formalising the corporation’s policies and for overseeing and enforcing the execution of these policies, such as through rewarding those (e.g., lower-level workers) who act in line with those (e.g., lower-level workers) policies and punishing those who act against those policies.

The second form holds that collective actions are brought about by plural subjects. Plural agents are brought about by a joint commitment to form a plural subject — a kind of collective agent — and through that joint commitment members of the collective endorse the attitudes and actions of the collective. These might be the attitudes and actions of an individual member of the collective — such as a political leader — but then each member of the collective stands behind those attitudes and actions and takes them to be attitudes and actions of the collective. This kind of account of collective agency can make sense of collective action that doesn’t stem from a formal decision-making process. As long as there is a joint commitment, people cannot dissociate themselves from an attitude or action of the collective action.

The third conception is The Membership Conception, according to which collective actions are those that speak for the collective. This can include actions performed by the collective, or ones performed by individual members of the collective. The key uniting factor is that the action aims, in some sense, to determine or influence what people — including both members of the collective and those who are not members of the collective — take the attitudes of the collective to be. Actions that result from a formal decision-making process associated with the group – such as a government’s policies – are ones that aim to speak for a nation. This is part of why people often protest their government’s decisions.

Not only are they trying to get the government to undo the policies in question, but they are also making clear that they do not want these policies to speak for them in their capacity as fellow members of the nation.

Perhaps The Agential Conception seems necessary because of cases where people do not causally contribute to some event coming about yet still seem to bear some responsibility for it. However, The Membership Conception can arguably make sense of these cases. Actions that result from a formal decision-making process or from an exercise of plural agency seem to also be ones that aim to speak for the group. Members of the group that do not approve of the actions of another member of the group may be motivated to speak out against the actions performed by the group, aiming to make clear that these action to really represent what each person thinks. In doing so, they concede that these are, in some sense, an action of the collective – at least for the time being.

This does not just apply to actions that result from a formal decision-making process. Consider how some Oxford University academics responded to Nigel Biggar when he published a newspaper articled where he said that that British people should not feel guilty for their colonial history. While these Oxford University academics wanted to clear up some misconceptions and mistakes that they believe underlie Biggar’s view, part of the function of their response is that it helps to change people’s perceptions of Oxford University academics as a group and, by association, Oxford University as an institution. So, even if Biggar did not intend to speak for Oxford University academics and Oxford University itself, his words were taken that way, or at least some other Oxford Academics worried they would be taken that way.

I propose we can think of both actions – Biggar’s writing and the response from some Oxford Academics – as kinds of collective action, namely as a steering actions, as they aim to steer the attitudes of the group (regardless of the intentions of the group member who performs that action) through shaping perceptions of the group’s attitudes. In effect, this kind of collective action centres on an identity-constituting narrative about a group, and often involves a power struggle between competing subgroups, a power struggle that may never be settled.

While some might wish to argue for a single kind of collective action, I think we should be pluralists about collective action. In my view, it can include any of the four options given above. There might be other kinds of collective actions that I’ve not discussed here. For the moment, I’ll focus on just these three conceptions.

The Nature of Collective Guilt

With the various conceptions of collective action in hand, we can see four different ways that collective guilt might be rational in a particular kind of way — namely, what philosophers often refer to as an emotion or attitude being fitting.

To say an emotion is fitting is to say that it accurately evaluates it object. For example, fear is fitting if it is felt about something that is fearsome (e.g. a dangerous bear). Guilt is fitting if it is felt about something that is worthy of guilt — namely, (i) something that one has done, and (ii) what one has done is substandard (by someone’s lights). It might seem that (i) cannot be met in collective cases.

First, consider contributory cases. It is not the case that an individual person has done something. Rather, they are simply contributed towards something coming about. Guilt may therefore only seem to be fitting for one’s contributions. Of course, though, guilty feelings are not just fitting for things we have done, but also for things that arise from things we have done. Suppose a person alone pushes a boulder down a hill and it crushes a person’s leg as it rolls down the hill. Guilty feelings are fitting not just for recklessly pushing the boulder, but also for its consequence: the crushing of the person’s leg. In the collective case, then, guilt may be fitting not just for our contribution to push the boulder, but also for the boulder rolling down the hill, as well as any further consequences of this (such as any injuries it causes).

Second, consider agential cases. There are many constituent members who have not themselves contributed to bringing about an action. Consider a corporation that pollutes a river by recklessly deciding to release toxic materials from its factory in order to dispose of them. Suppose that this was the result of a policy agreed to by the management of the corporation. Such a policy might be put into place even if not all of the corporation’s mangers agree with the policy. These dissenting managers haven’t actually done anything to bring about the policy and have even tried to stop it being put in place. So, what do they have to feel guilty about? One might argue that even as dissenting managers, they are members of a formal decision-making process and so must also accept what results from this process as being actions that they are implicated in. They may not have contributed to bringing about the policy and its resulting harms, but they arguably still help to bring about the policy by taking part in the decision-making process that led to the policy being put in place.

Third, consider membership cases. A person born long after an atrocity was committed did not, and could not have, been involved in bringing about that atrocity (except if they someone had a time machine, but raising this kind of potentially merely conceptually possible scenario in order to force a distracting caveat to be made explicit is why philosophers often don’t get invited to parties). Guilt therefore seems unfitting for this person to feel. But this overlooks that people can be members of groups that have, before any particular member was born, committed an atrocity — whether through the group working together or a single member of the group doing so. When a person is a member of a group, they can fittingly feel guilty about the actions performed by that group. You might then wonder: what makes someone a member of a group? I won’t go into this question here, as I plan to talk about in a future post. For the moment, we can just take for granted that people are part of groups — whether they are national, ethnic, religious groups, value-based groups, or other kinds of groups. Here I’ll focus on national guilt, as it is the most discussed kind of collective guilt outside of philosophy.

A key advantage of membership guilt is that it provides a way to explain why guilt for historical injustices can sometimes be fitting. It also has the advantage that it explains the guilt that citizens may feel for their nation’s actions regardless of their power they have or don’t have to control the politicians or policies that led to those actions. This is crucial given that national guilt is the kind of collective guilt that most commonly gets discussed outside of philosophy. (It’s a shame, then, that philosopher’s sometimes consider such “membership guilt” to not be a kind of collective guilt.)

Finally, even if you’re inclined to think guilt about your country’s past is completely irrational, this commits you to also rejecting the rationality of pride about your country’s past. Likewise, if you’re inclined towards accepting that guilt about your country’s past is may be rational, this commits you to also accepting that it may be rational to feel pride about your country’s past.

Individual Guilt: Emotion vs Experience

How can we distinguish between instances of collective guilt that are valuable and ones that are dangerous? I suggest that this depends on how we attend to feelings of collective guilt.

I ended my first post with the following:

Finally, I think that attending to guilty feelings in a morally appropriate way will sometimes lead to feelings of regret (wishing to undo the wrong), remorse (taking up the victim’s perspective), blame (holding the wrong against ourselves), and shame (finding fault in ourself, i.e. our attitudes, character traits, etc.). We might, then, be able to distinguish between the emotion of guilt (which I’ve focused on until this paragraph) and the morally appropriate experience of guilt (which I’ve suggested the contours of in this paragraph).

The emotion of guilt is short-lived, felt in response to immediate stimuli, and may dissipate without further reinforcement. The morally appropriate experience of guilt, on the other hand, is more complex: it may initially involve the emotion of guilt, but as we attend to the perceived causes of our guilt, we can then begin to feel regret, remorse, shame, and blame ourselves for what we have done (or we may come to feel resentment or anger if we feel we have been unjustifiably made to feel guilty, but I’ll see aside these cases for the moment). While guilt the emotion has its own action tendency, guilt the experience has a range of action tendencies, ones associated with the emotions that can make up the experience of guilt.

Let’s consider how this works in individual cases. When a person feels guilty, they have appraised something they have done as substandard. They then feel bad in the way that is distinctive of guilt. This then motivates them to get rid of their guilt, either through robust repair, hollow repair, defensiveness, or suppression. How they are motivated to act, I propose, depends on how they attend to their guilty feelings.

We might come to focus on the standard we have violated. We might judge (rightly or wrongly) that it is an illegitimate standard. We might then, because of the dynamics of the social situation, offer a hollow apology because this is the easiest thing to offer in this situation. We might instead get defensive, and so try to undermine the reasons someone has for making us feel guilty. If we have made ourselves feel guilty, but judge the standard to be illegitimate, we might even try to undermine our own reasons (if the judgement the standards are illegitimate is not enough to remove our guilty feelings). For example, you feel guilty for failing to meet a self-imposed deadline and you then convince yourself this was an unreasonable expectation to hold yourself to such that you no longer feel guilty for your failure.

Or we might judge we’ve failed in a way that violates a legitimate standard. We might then judge that we cannot face our feelings of guilt. Perhaps it is just too much to cope with. This can motivate suppressing our guilty feelings. This might be done through drinking a lot of alcohol or taking drugs. Both are ways of redirecting our attention onto other matters, or even just make us unable to pay attention to anything at all. We can often achieve this without intoxicating ourselves. We can instead simply redirect our attention towards other things, hoping that our guilty feelings will eventually dissipate.

We might instead face the fact we’ve violated (what we take to be) a legitimate standard. When we accept this, we are more likely going to trying to repair our violation in a robust way. We may wish to undo the wrong, and so come to feel regret. The hope being that undoing the wrong will repair what we have done. More often than not, though, undoing the wrong is either impossible (what we have done cannot be fixed as easily as replacing something we’ve broken) or undesirable (undoing what we did, if it were possible, would have more harmful ramifications; for historical injustices this may even include leading to our non-existence). Regret, then, may be rationally limited while we discover either its impossibility or undesirability. Of course, though, we may still continue to feel unfitting regret in the admirable hope that we can somehow either do the impossible or avoid the undesirable consequences of undoing what we did.

Just because negating a harm may be impossible or undesirable, this does not mean that we cannot do the next best thing and find a way to counter-balance what we have done. If our focus is on how violated standard may have impacted others, we might try to take up their perspective to understand how we have harmed them. Such perspective taking following a failure is a key part of feeling remorse. We can come to see the extent to which we have harmed people following our failure, and so find ways to counter-balance what we have done.

One part of counter-balancing the harm is to blame ourselves. Unlike guilt, blame takes both what we’ve done or failed to do (the failure) and ourselves as its object. When we blame ourselves, we take ourselves to be blameworthy. Blameworthiness is a property of a person, and not (strictly speaking) a property of an action. In my view, blame involves holding an action against a person. So, when we blame ourselves, we hold an action against ourselves. This can involve being angry with ourselves, being disappointed with ourselves, or holding ourselves to obligations we’ve incurred through our failure, such as an obligation to apologise, and an obligation to remember what we’ve done.

Holding what we have done against ourselves also turns our attention towards us rather than just on what we have done (or failed to do). If properly focused, this will inevitably lead to us judging that part of our self — an attitude, a character trait, or a set of these — is also implicated in the failure. Our actions, after all, arise at least in part from parts of our self (while some things we do are sometimes said to be out of character, nothing we do is ever out of self). A key part of feeling shame is judging that a part of our self is substandard. So if we have such a judgement about a part of our self — some of our attitudes or traits, for example — we may then feel shame for what we have done through feeling ashamed of these attitudes or traits.

Now, in order to get rid of our guilty feelings and the feelings that come along with the experience of guilt, we may have to get rid of regret, remorse, blame, and shame. This requires more than just a hollow apology. And even a robust apology will likely be limited in most cases. It is one thing to promise sincerely that you will change, and it is another thing to actually change. So, it seems that we will often need to transform, in the relevant respects, such as that we are no longer able to fail in the kinds of way we failed. As I argue in earlier publications (and this earlier cross-post), transformation is one part of ceasing to be blameworthy.

Transformation would also undermine our grounds for feeling shame. If shame is fitting because we have some substandard aspects of self, it ceases to be fitting once we have transformed ourselves appropriately. Remorse may continue to be fitting as long as we need to take up the perspectives of those harmed by what we done (or failed to do). Presumably, this would cease to be fitting once we have ceased being blameworthy.

Ceasing to be blameworthy not only requires transformation, though. It also requires meeting all the obligations one has incurred through failing. Such obligations include communicating that we have changed and met such obligations. It often also includes a duty to remember what we’ve done. Once we have done all this, we have rectified what we have done and redeemed ourselves. We cease to be blameworthy and so blame ceases to be fitting.

There are two things it’s worth emphasising here. First, it might be really hard to actually cease being blameworthy for anything beyond minor failures. So, the fact ceasing to be blameworthy is (metaphysically) possible does not mean it is likely or easy to accomplish. Second, even if we manage to cease being blameworthy, we may still continue to feel negative emotions (and emotion-laden attitudes) such as regret, remorse, shame, and blame. That we do so may even be part of what it means to be redeemed. Such continued feeling of, what are now, unfitting emotions may help us to stay redeemed by helping us to continue to remember what we did. Even so, it seems that at some point it will no longer be valuable to keep feeling such unfitting emotions. It is, though, hard to stay precisely where these emotions are no longer even valuable to feel.

Collective Guilt: Emotion vs Experience

Let’s now see how this applies to collective guilt and, in particular, collective guilt for historical wrongs. When we a person feels national guilt, they are feeling it in response to something that their nation has done. The person must have appraised something their nation did something substandard. The relevant action, then, must belong to the nation. This might be something the nation’s military did, or even just what one particular citizen did. The person then feels bad in the way that is distinctive of guilt. This then motivates them to get rid of their guilt, either through robust repair, hollow repair, defensiveness, or suppression. How they are motivated to act, I propose, depends on how they attend to their guilty feelings.

They might come to focus on the standard the nation has have violated. They might judge (rightly or wrongly) that it is an illegitimate standard. They might then, because of the dynamics of the social situation, offer a hollow apology because this is the easiest thing to offer in this situation, e.g., “Oh I’m so sorry about my ancestor’s enslaving all your ancestors”. We might instead get defensive, and so try to undermine the reasons someone has for making us feel guilty, e.g., “it was a different time! People had different values back then; stop trying to make me feel guilty about this!”.

Or we might judge our nation has failed in a way that violates a legitimate standard. We might then be unable to face our feelings of guilt. Perhaps it is just too much to cope with. This can motivate suppressing our guilty feelings. We may simply redirect our attention towards other things, hoping that our guilty feelings will eventually dissipate. For example, we might just not think about our country’s past anymore.

We might instead face the fact our nation did very wrong things in the past. When we accept this, we are more likely going to trying to repair the failure in a robust way. We may wish to undo the wrongs our nation committed, and so come to feel regret. The hope being that undoing these wrongs will repair what our nation did. Again, though, undoing the wrong may be either impossible (what our nation has done cannot be fixed as easily as replacing something we’ve broken) or undesirable (undoing what our nation did, if it were possible, would have more harmful ramifications, such as leading to our non-existence). Regret, then, may be rationally limited while we discover either its impossibility or undesirability. Of course, though, we may still continue to feel unfitting regret in the admirable hope that we can somehow either do the impossible or avoid the undesirable consequences of undoing what we did.

Just because negating a harm may be impossible or undesirable, this does not mean that we cannot do the next best thing and find a way to counter-balance what we have done. If our focus is on a national failure and how it may have impacted others, we might try to take up the perspectives of those were impacted by that failure to understand more fully how they were harmed by our nation. Such perspectivee taking following a failure is part of feeling remorse. We can come to see the extent to which our nation has harmed people, and so find ways to counter-balance what our nation has done.

One part of counter-balancing the harm is to blame our nation. Unlike guilt, blame takes both what our nation has done or failed to do (the failure) and our nation as its object. When we blame our nation, we take our nation to be blameworthy. Importantly, we are not taking a third-person perspective when we blame our nation. Rather, we are blaming it from within. So, we are not saying: “this nation did something wrong and this counts against it”. We are rather saying: “we did something wrong and this counts against us”.

Holding what our nation has done against itself also turns our attention towards our nation rather than just on what our nation has done (or failed to do). If properly focused, this will inevitably lead to us judging that part of our nation — an institution, a citizen, an attitude of the nation, or a set of these — is also implicated in the failure. (In my view, institutions are ultimately reducible to attitudes of members of the nation, but I won’t argue for this here; the basic idea, though, is that institutions are made up of rules but those rules require the attitudinal endorsement of members of the institution — this is a lesson of Little Miss Sunshine. We will then come feel shame for what we have done through feeling ashamed of these attitudes or traits.

Now, in order to get rid of our guilty feelings about our nation’s past and the feelings that come along with the experience of guilt, we will have to get rid of the national regret, remorse, blame, and shame that we experience along with a morally appropriate form of national guilt. This requires more than just a hollow national apology. It is unlikely that any kind of apology for a mere member of a nation would be enough. And even a robust apology will likely be limited in most cases, even one from a political leader of the nation. It is one thing to promise sincerely that the nation will change, and it is another thing to actually change it. But change is typically required: the nation will often need to transform, in the relevant respects, such as that it is no longer able to fail in the kinds of way it has failed.

As with individual guilt, transformation of the nation — changing its institutions, its citizens, or (and I think most importantly) its attitudes — would also undermine our grounds for feeling national shame. If national shame is fitting because have some substandard aspects of our nation, it ceases to be fitting once we have transformed our nation appropriately. Remorse may continue to be fitting as long as we need to take up the perspectives of those harmed by our nation. Presumably, this would cease to be fitting once our nation has ceased being blameworthy.

The reparative obligations that go along with blameworthiness also need to be met. This includes material and symbolic compensation for harms committed by our nation, as well as a duty to remember what our nation has done. Once all this has been done, what our nation has done will have been rectified and our nation will be redeemed. And I think the nation would then cease being blameworthy for what it did earlier in time — though questions of national responsibility and state’s culpability through time raise more complicated question that I can’t get fully into here, so I’m just going to take this for granted here.

In the national case, given the gravity of the wrongs that may be in question, it may not be easy for the nation to cease being blameworthy. But, unlike individuals, one thing that nations have on their side is time. Nations typically exist much longer than a person does and so there is much more time for the nation to repent, rectify its wrongs, and redeem itself. Moreover, such redemption can be achieved through not just the efforts of individual people, but groups of people. So, while achieving national redemption may be hard, it is in another way made easier by the fact that nations have both time and more people on their side.

The Value and Dangers of Collective Guilt

The key value of collective guilt, as I see, it is that it can encourage us to focus our attention on historical wrongs, and then it can help to rectify those wrongs. It does so through helping to shape the dominant national narrative about how we should understand these wrongs. Changing this dominant national narrative can then encourage (where appropriate) material and symbolic reparations, national apologies, and formalised remembrance practices.

For example, on December 7, 1970, the then West German Chancellor Willy Brandt fell to his knees in front of a monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In his memoir, he offered the following brief explanation of his action:

I had not planned anything, but I had left Wilanow Castle, where I was staying with a feeling that I must express the exceptional significance of the ghetto memorial. From the bottom of abyss of German history, under the burden of millions of victims of murder, I did what human beings do when speech fails them. (Brandt 1989/1992: 200)

He also quotes (without attribution) a journalist’s description of his action:

‘Then he who does not need to kneel knelt on behalf of all who do need to kneel but do not – because they dare not, or cannot, or cannot dare to kneel’ (Brandt 1989/1992: 200)

Among other things, I think Brandt’s act expresses collective guilt. While there were mixed feelings about his knee fall from Germans polled at the time about it, Brandt’s knee fall has been credited with helping to change the dominant national narrative about Germany’s Nazi past.

But collective guilt isn’t without its dangers. Here are a few.

First, a person might feel such guilt even though they shouldn’t, and thereby help to shape their national narrative badly.

Second, just because a person feels collective guilt, it doesn’t mean they will attend to it well. Some dangers arise from not responding well to feelings of collective guilt, such as trying to suppress your feelings or being defensive and attacking those who you feel are trying to provoke guilty feelings.

Third, feeling guilty about your nation’s past can become part of a person’s identity. While that may lead to a person focusing on attempting to rectify their nation’s past, it may also lead the person to dwell on the historical wrong without striving to repair that wrong. Such a person, then, may dwell in the negative feelings partly constitutive of guilt, perhaps with the thought they deserve to feel the pain of guilt, but without that guilt doing anything of value — such as helping the nation to repent, rectify its wrongs and redeem itself.